Ultra-Processed Foods: Are they as dangerous as we are led to believe?

The controversy surrounding ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has been a hot topic in recent years, attracting media attention and sparking debate among health professionals, policy makers, and influencers! It’s not uncommon for UPFs to be labelled as “toxic” or “dangerous”, painting a rather grim picture. But is the situation as dire as it seems?

As a Registered Nutritionist, I’ve been asked countless times about the health implications of UPFs. Are they as perilous as they’re made out to be? Should we steer clear of all processed foods? Is this alarming narrative about UPFs constructive in promoting public health? Much of the attention on this topic is very one-sided, so I wanted to write this blog from a more balanced perspective. Hopefully this will be more helpful than what is usually reported.

First things first, what exactly are they?

What Are Ultra-Processed Foods?

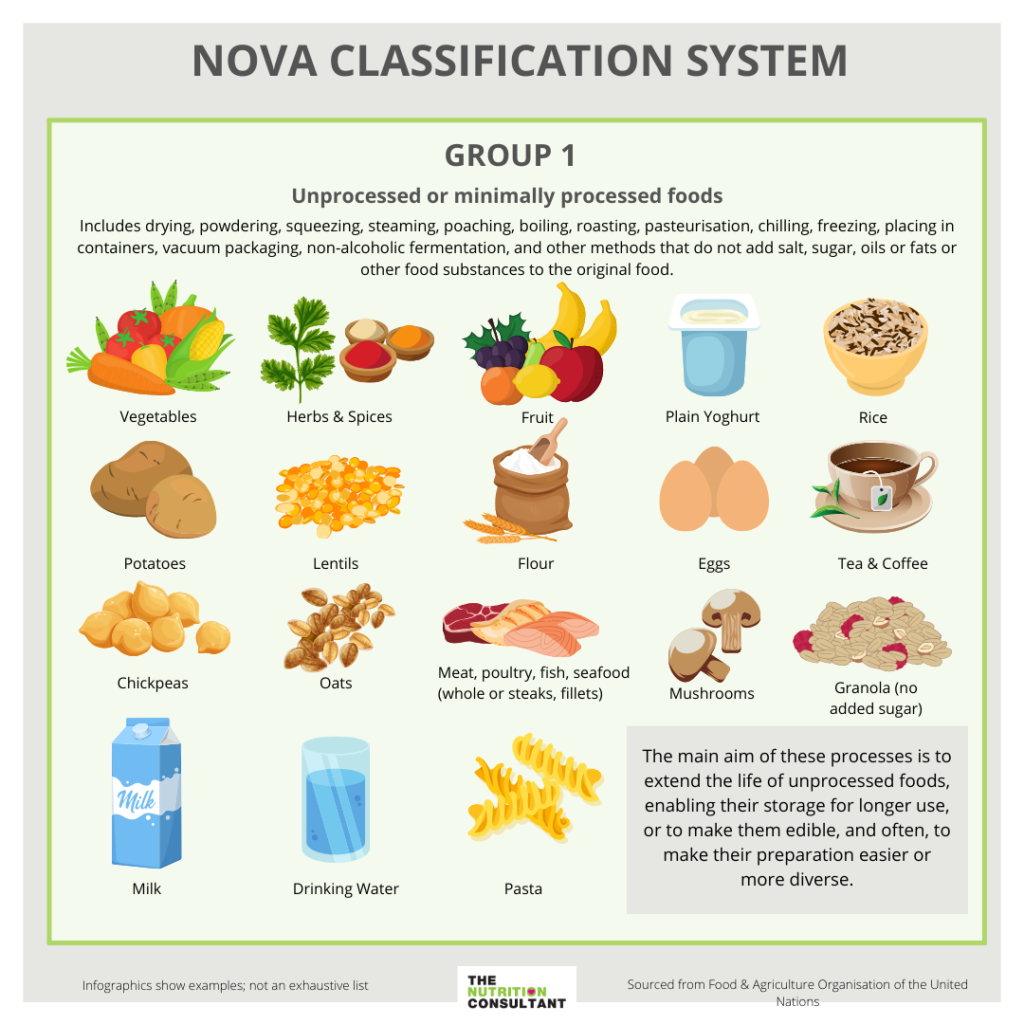

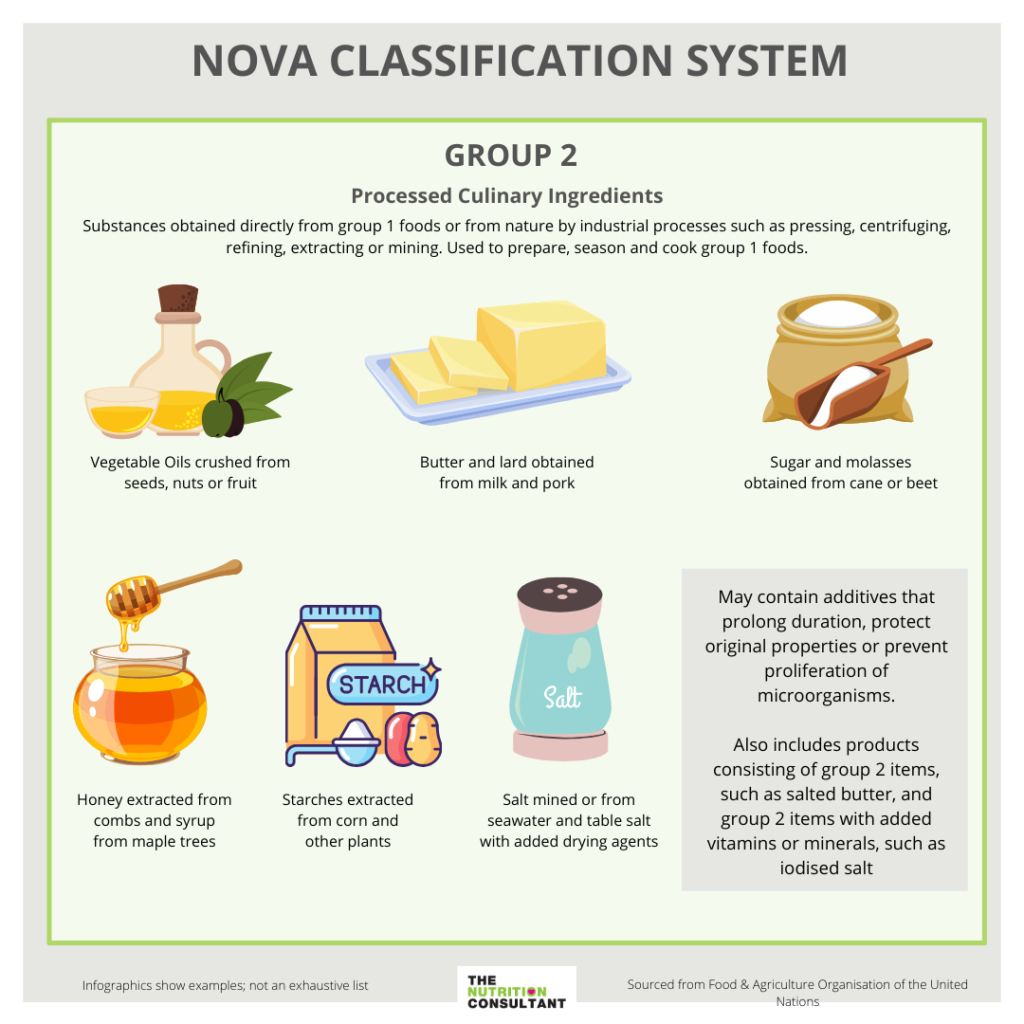

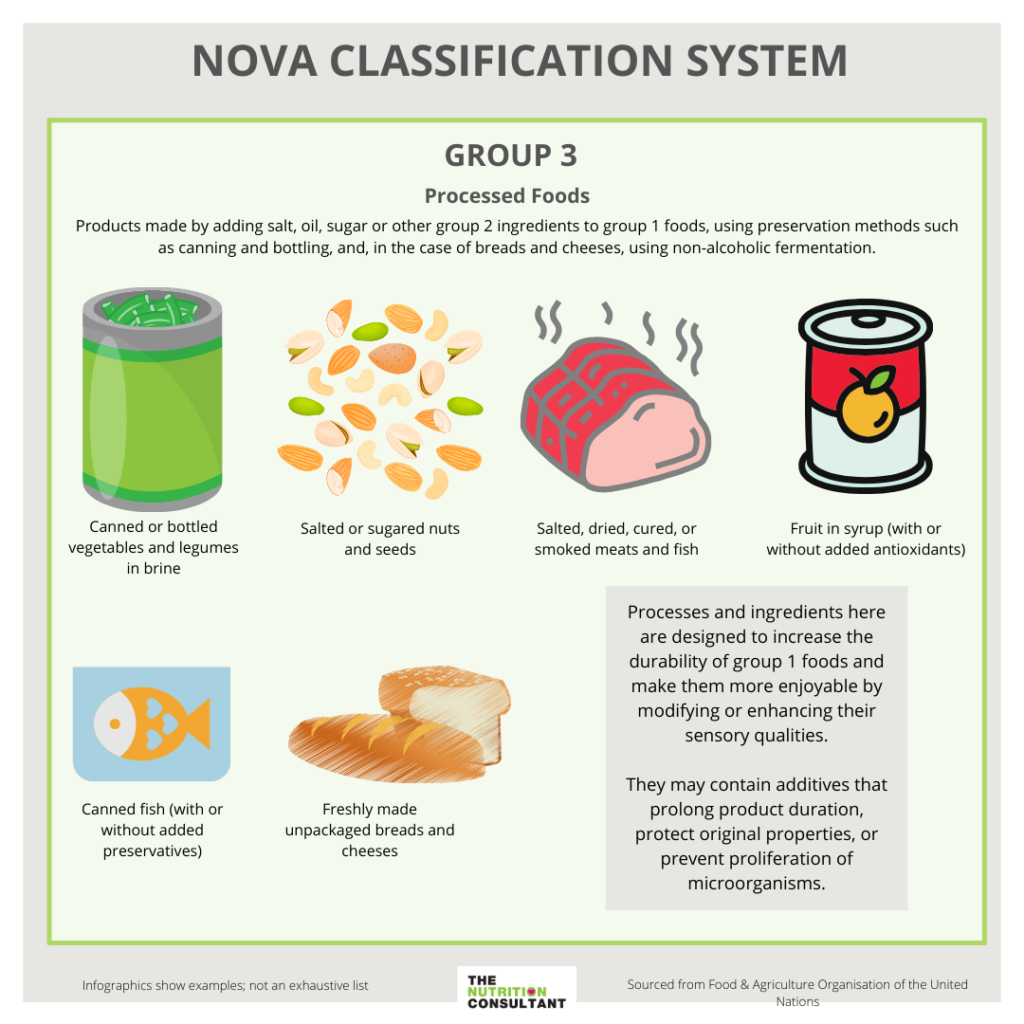

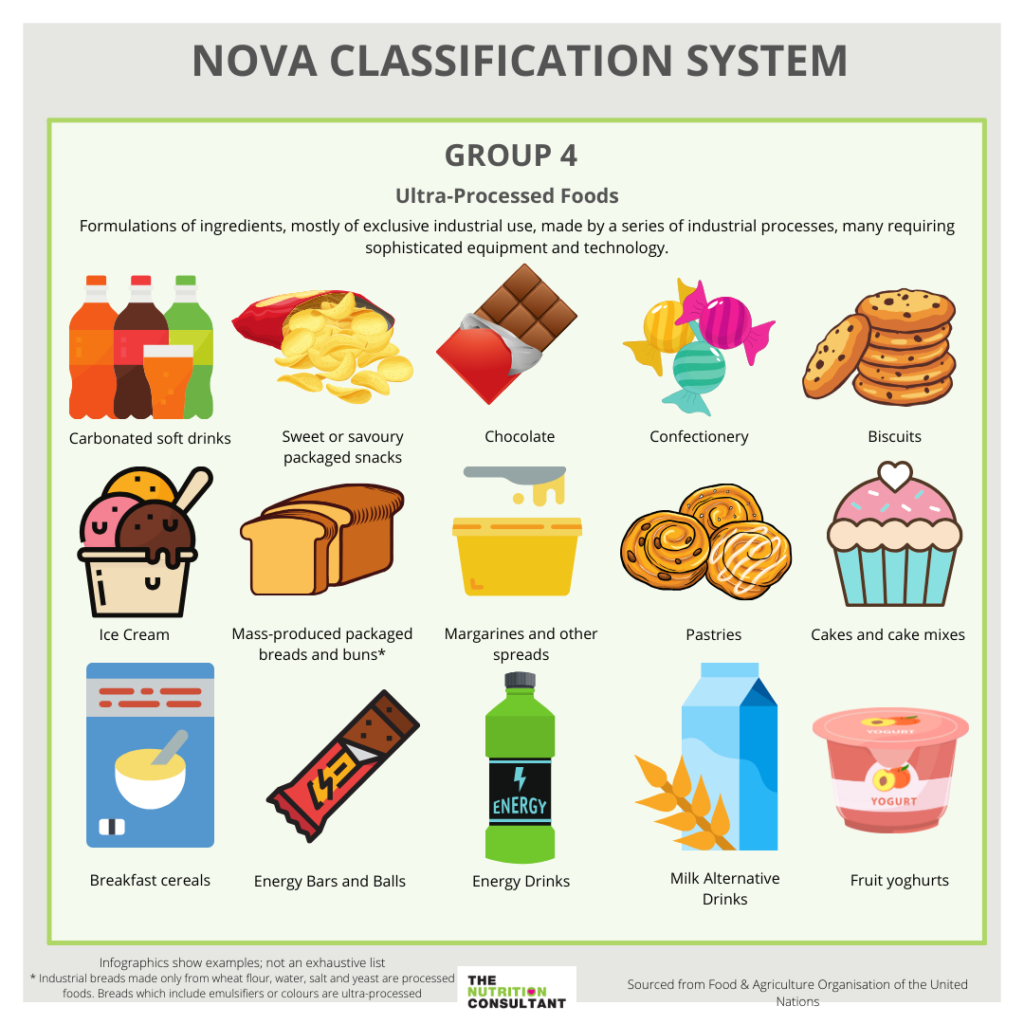

The degree of processing varies across various foods. Although a universally accepted classification is yet to be established, the NOVA classification is widely recognized. It categorizes foods into four groups based on the extent of processing ranging from unprocessed or minimally processed foods to ultra-processed foods (UPFs).

- Unprocessed or minimally processed foods

- Processed culinary ingredients

- Processed foods

- Ultra-processed foods (UPFs)

UPFs are typically made up of numerous ingredients that are often extracts from whole foods such as sugar, oils, fats, and proteins. These ingredients are then combined with additives like colourings, flavourings, and emulsifiers to produce foods that are not only highly palatable and visually appealing, but also have a long shelf life.

UPFs usually include items such as,

- Chocolate

- Packaged snacks (sweet or savoury)

- Biscuits

- Mass-produced packaged breads and buns

- Margarines

- Pastries, cakes and cake mixes

- Fruit yoghurts

- Ice cream,

- Breakfast cereals

- Carbonated soft drinks or energy drinks

- Milk alternative drinks

- Infant formulas and follow on milks

- Meal replacement shakes and powders

- ‘Instant’ soups, noodles and desserts

- Ready meals and convenience products like pies, pizza, sausages, chicken nuggets and other reconstituted meat products.

How Much Ultra-Processed Food Are We Consuming?

A lot!

According to recent data, the average adult in the UK is consuming 51% of their calories from UPF’s. This increases even more when we look at children (1.5-11 years) and teenagers (12-18 years), as UPF’s make up 63.5% and 68% of their daily calorie intake respectively (1).

The Nutritional Value of UPF’s

But the question remains – are ultra-processed foods really that detrimental to our health?

Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) are often, though not always, low in nutritional value and dense in calories. Research consistently demonstrates that diets high in UPFs tend to be deficient in essential elements such as fruits, vegetables, fibre, and protein. Instead, they tend to be high in salt, fat, saturated fat, and sugar (2).

So, it’s no surprise that numerous studies have established a clear connection between excessive UPF consumption and chronic disease (3).

UPF Intake and Poor Health

Observational studies in adults have shown that a high intake of UPFs is associated with an increased risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, cancer, irritable bowel syndrome and depression (3).

However, it’s crucial to approach these findings with a critical eye. Whilst these studies suggest a correlation between UPFs and health issues, we must be wary of jumping to conclusions about direct causation. They are observational studies, which means that whilst a link exists between UPFs and health issues, we must exercise caution in drawing direct causation.

It’s possible that factors beyond UPFs, such as socioeconomic status, are strongly intertwined with UPF intake, influencing the observed health outcomes. Therefore, whilst these studies provide valuable insights, the full picture requires further exploration through more robust research methods such as randomised controlled trials (RCT).

RCT: Ultra-Processed vs Minimally Processed Diet

To date, there has been one RCT that has studied the effect of an ultra-processed diet on health outcomes (4).

During this study, participants were given either ultra-processed or minimally processed foods for two weeks, both sets of meals being matched in terms of macronutrient content etc. Then they swapped to the other diet for another two weeks. The study allowed participants to eat as much or as little as they desired.

The results were conclusive: participants consumed an average of 508 extra calories daily when consuming ultra-processed foods, leading to an average weight gain of 0.9kg, while losing the same amount on the minimally processed diet. This reinforces the notion that ultra-processed foods, due to their high palatability, can lead to overconsumption and subsequent weight gain and obesity-related health issues.

In our world where ultra-processed foods dominate our food environment and are heavily advertised, it’s understandable why many individuals feel “out of control” around these types of processed foods. However, this study only demonstrates the impact of a diet exclusively made up of ultra-processed foods, which doesn’t reflect the reality of most people’s diets that are a mix of ultra-processed foods and minimally processed or unprocessed foods.

Do Ultra-Processed Foods Have a Place In Our Diets?

The short answer is, absolutely, but to an extent.

Consuming whole foods most of the time is beneficial, but that doesn’t mean ultra-processed foods aren’t important. They have a role in modern society and have some benefits that are often overlooked.

Benefits of UPFs

1.Without UPFs, our population would be more at risk of nutrient deficiencies.

This may be hard to believe, but for a moment let’s consider just how many foods fall into the UPF category.

Not only does it include cakes and ready meals, but it also includes household staples such as breakfast cereals, infant formulas and follow on milks, milk alternative drinks and mass-produced bread – all of which are usually fortified with vitamins and minerals to help fill nutritional gaps within the population.

In fact, some nutrients are legally required to be added to foods during processing to help certain populations meet dietary recommendations.

- Breakfast cereals – Many cereals are fortified with additional nutrients such as iron, vitamin D and calcium to help children and adults meet the necessary recommendations. Some low-sugar cereals such as Weetabix or Shredded Wheat make an affordable, high fibre breakfast option.

- Infant formula and follow on milks – These provide essential nutrition for babies and children where breastfeeding is not possible. Without these products, these children could suffer from significant development problems and long-term health consequences.

- Plant-based milks – Important products for people avoiding dairy as they are usually fortified with additional nutrients to resemble the nutritional properties of milk.

- Mass-produced bread – It is a legal requirement that all white and brown (non-wholemeal) breads made and sold in the UK have calcium, iron, thiamine and niacin added to them. As this bread is affordable and widely accessible, this can help reduce the risk of nutrient deficiencies in poorer communities and for those with limited diets.

To give an example of how impactful these food staples are: in the UK, the ‘cereal and cereal products’ food group, which includes UPFs such as fortified breakfast cereals and mass-produced breads, is the biggest contributor towards dietary iron intake across all age groups. In fact, these food products provide half of a child’s daily iron intake and is the greatest source of calcium for older children (1).

So, if we were to remove all UPFs from the food system tomorrow, we might be successful in reducing our sugar intake, but we could also risk increasing specific nutrient deficiencies within the UK population, especially in children.

2. Accessibility of foods to wider populations would be limited, including those who live in poorer communities.

Feeding a large population would be difficult without some level of UPFs, especially with the recent cost of living crisis.

Processing can help reduce food waste, it can be a cheaper source of calories and nutrients and allows food to be stored longer.

It would be amazing if everyone could afford to buy fresh, minimally processed foods without worrying about them going off too quick, but unfortunately this just isn’t possible in a world where food banks are reaching record highs.

3. Including some UPFs can help us eat better overall.

People are always looking for a shortcut in the kitchen and whilst cooking everything from scratch would be ideal for reducing sugar, salt, and saturated fat intake, this isn’t possible for most people at every meal.

Convenience products like pre-made sauces may fall under the UPF category, but they can be easily paired with more nutritious foods like vegetables and lean meats to speed up meal preparation.

Using a jar of pre-made curry sauce shouldn’t detract from the nutritional value of a chicken and vegetable curry, because it still offers a variety of nutrients like fibre, protein, vitamins, and minerals.

4. We wouldn’t have the variety of food options we have today.

Food isn’t just for nourishment – it also brings people together and adds joy to our lives.

Of course, day-to-day overconsumption of UPFs is not beneficial for our health but eliminating this large group of foods because of their processing level could lead to a more negative relationship with food, causing stress and anxiety at mealtimes and making social occasions less enjoyable.

This is why I think we need to be more cautious about casually labelling UPFs as “toxic” or “dangerous”, because this doesn’t take into consideration the importance of balance within a healthy diet.

There is a place for all foods in a healthy balanced diet, it’s just finding the right balance.

A Problem With the Definition of Ultra-Processed Foods

The main problem with the term ‘Ultra-Processed Foods’ is that it encompasses a broad range of foods based on their level of processing, which can be misleading as two foods with similar processing levels can have significantly different nutritional values.

For example, there is no distinction between a high fibre, low sugar cereal fortified with essential vitamins and minerals, and a high sugar cereal with minimal fibre that’s not fortified. Both are classed as UPFs, but one contributes significantly more to someones daily nutritional intake.

It would be more beneficial to categorize foods based on the nutrients they contain. In the UK, HFSS food and drinks (meaning those high in saturated fat, sugar and salt) are the main focus of many policies aiming to improve public health.

Unlike UPFs, the research around HFSS foods is based on a breadth of evidence that shows that diets high in saturated fat, sugar and salt can have a negative impact on our health.

Final Thoughts

Focusing on the level of added ingredients such as salt, sugar, saturated fat and additives in foods is more important than vilifying foods based on their level of processing.

In addition, attempting to define healthy foods solely based on their processing level is counterproductive. Many UPFs are household staples that help individuals meet their nutritional recommendations and they enable families to frequently put meals on the table during the strain of the cost-of-living crisis.

It’s also concerning to see terms like “toxic” and “dangerous” attached to UPFs. The reality is that all foods have a place within a balanced and healthy diet, but the key lies in striking the right balance. Understanding these nuances in nutrition is important, and using sweeping statements like these could do more harm than good in helping people develop healthier eating habits and foster a positive relationship with food.

Demonising UPFs is not a constructive solution for improving population health. What we need is a whole systems approach that aims to mend our broken food system, which includes increasing the affordability and accessibility of nutritious foods, improving the nutritional properties of convenience foods, and focusing on the health of the younger generations. By addressing these aspects collectively, we can start paving the way for a healthier future for all.

References

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2023). SACN Statement on Processed Foods and Health: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1168948/SACN-position-statement-Processed-Foods-and-Health.pdf

- Adams, J. and White, M. (2015). Characterisation of UK diets according to degree of food processing and associations with socio-demographics and obesity: cross-sectional analysis of UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–12). International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 12(1), pp.1-11.

- Lane, M.M., Davis, J.A., Beattie, S., Gómez‐Donoso, C., Loughman, A., O’Neil, A., Jacka, F., Berk, M., Page, R., Marx, W. and Rocks, T. (2021). Ultraprocessed food and chronic noncommunicable diseases: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 43 observational studies. Obesity Reviews, 22(3), p.e13146.

- Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (2023). SACN Statement on Processed Foods and Health: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1168948/SACN-position-statement-Processed-Foods-and-Health.pdf